This post originally ran with The Atlantic.

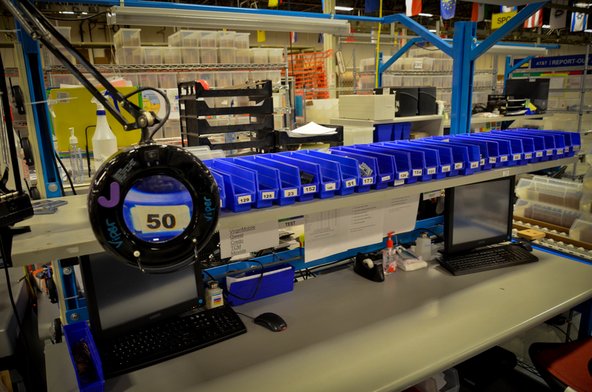

The first thing I noticed when I stepped into Recellular’s Ann Arbor warehouse was the flags. From the rafters, dozens of flags of the world oversee the processing of more than four million cell phones each year. Algeria and Mali keep watch as donated phones are sorted by make and model into row after row of labeled plastic trays. Brazil and Poland command dozens of test benches, where workers inspect, clean, and repair used phones for resale. Puerto Rico and Great Britain hang over the upstream holding area, where hundreds of used and refurbished phones wait in addressed boxes to be shipped out to customers. Each flag represents an employee—they add a new flag every time they hire someone from another country.

The flags also emphasize the company’s global impact: when you donate a phone to Cell Phones for Soldiers, or Sprint Project Connect, or The March of Dimes, it will end up here. Lots of people think that when they donate to Cell Phones for Soldiers, the phone is actually mailed to Iraq. That wouldn’t work very well—our locked down handsets would be rather worthless on Iraq’s cell networks. Instead, Recellular resells or recycles the phone and uses some of the profits to buy calling cards for soldiers. The man behind Recellular is the inimitable Chuck Newman. Chuck and his Recellular team recycle over ten thousand used phones every day, which they claim is more than any other cell phone recycler in the world.

Chuck and his brother Allan founded Recellular in 1991, the same year that cell phones switched from analog 1G signals to the digital 2G network. The Newman brothers recognized a trend—people were beginning to upgrade to new cell phones not because their old phones were broken, but because advances in technology had made them obsolete. In this high tech trash, Chuck and Allan saw an opportunity to start a business and to protect the environment—by refurbishing, reusing, and recycling the millions of phones that would have otherwise sat in drawers for years.

The business model proved highly successful. It’s news to nobody that the vast majority (83%) of American adults have some sort of cell phone. Worldwide, 1.6 billion cell phones were sold last year. Although people are hanging onto their phones for slightly longer today than they were a few years ago—Americans reported keeping their phones an average of 20.5 months in 2010, up 17% from 2009—most people still upgrade their phone more than once every two years.

I sat down with Chuck this week to discuss some of the larger issues surrounding cell phones. I’ve been studying the sources and consequences of electronics manufacturing for years and have traveled all around the world, visiting repair shops and e-waste sites. My company, iFixit, is dedicated to increasing the lifespan of our devices, and I value Chuck’s perspective on the issue.

Where does this growth stop, I asked? How many phones should we be making each year for a population of 7 billion people? Chuck isn’t sure that growth can or should be stopped:

In the capitalistic system, in the marketplace, the people decide what they need or want. It’s awfully hard to impose upon them, saying, “You don’t really need that.” We have the right to get a phone that’s smaller and a prettier color if we want. And I think it’s pretty clear that there are enormous economic and health benefits to populations having access to communications.

I am also a technology evangelist. The productivity benefits technology brings make our lives easier—but they can also lift someone out of poverty by making a fledgling business profitable. We’re just starting to see how pervasive communications are changing lives: it’s now possible for a fisherman in Mombasa to check from the docks which market will give him a better price and for a farmer in Haryana to receive life-altering weather updates via SMS.

It’s doesn’t do any good to have the capacity to manufacture a cell phone for every person in the world if they can’t afford it. The real way we to make affordable phones available to the masses is to get phones from people that are done with them to the people that need them.

Every day a phone sits in a drawer is a day it’s not being used by someone—and a day closer to compatible cell networks shutting off forever. We need to get the used phones from the drawers of Americans into the hands of people in the developing world. And Recellular is more effective at that than just about any other organization.

There’s a market for used phones in America, too. Many customers want nothing more than the ability to make calls and send text messages. Recellular’s biggest seller is still the original RAZR, which Motorola stopped manufacturing in 2007. AT&T, and perhaps some other manufacturers, have marketed their refurbished phones as “the eco-conscious choice.” “And that is just right,” Chuck emphasizes, “they are green phones.” Apple’s recently updated environmental site supports this claim; manufacturing accounts for 61% of electronics’ carbon footprint. That’s the same reason a used car is more environmentally friendly along some vectors than a Prius. Reuse is the simplest way to mitigate the environmental impact of manufacturing.

Many large cell phone manufacturers have placed Recellular collection bins in their retail stores to support their cell phone refurbishment programs. Yet only about 10% of defunct phones are recycled, and most people have at least a couple of old cell phones sitting around.

Why? Chuck boils it down to three major reasons (“this is part of my stump speech,” he quips with a laugh): first, people need to be aware that they have options for disposing their phone properly. Second, people need to be motivated to recycle. Third, recycling needs to be “really, really easy. Even when people have the best intentions,” he explains, “if it requires an action on their part, it’s pretty easy to forget.”

Even though it’s the reason they got into the business, ReCellular has learned that the environmental message isn’t very effective. Instead, they distribute postage-paid envelopes for people to send in old phones, donating them to some cause or another. When the envelope says the phone will be donated to charity, 50-80% more phones come in than when it bears a strong environmental message. Through their more than 2,000 charitable and environmental partnerships, they donated more than $3 million to charity in 2009.

The jobs Recellular has created in cell phone repair and reuse are a positive data point in an otherwise flagging Michigan economy. Much of the manufacturing that made the Rust Belt famous has moved overseas, but there’s still lots of money to be made—and jobs to be created—remanufacturing electronics. And through reuse and remanufacturing, Recellular makes the world a better place, getting phones to people who need them and helping charities such as Cell Phones for Soldiers reap the rewards.

0 Yorum